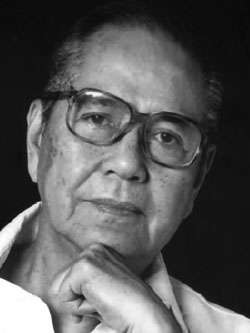

Renato Constantino

Historian, Nationalist

Among the strongest influences in his youth was his maternal grandmother who told him stories about the abuses of Spanish friars. Her family suffered during the early American occupation. His father was critical of politicians of his time for their corruption and lack of sincerity in fighting for independence. Renato's siblings reported that although their parents were strict and expected unconditional obedience, their brother would sometimes dare to argue with them when he did not agree with their opinions.

A product of the public school system, Renato emerged as a student leader during his third and fourth years in Arellano High School when he was elected class president and also won medals as an orator and debater. In the University of the Philippines he became the youngest editor of the Philippine Collegian and a star debater. He won national attention with an editorial critical of President Manuel Quezon which prompted the latter to go to UP to deliver a speech explaining his position.

Renato fought in Bataan and was later sent by G2 to Manila to join a group that was monitoring Japanese military movements and sending reports to Corregidor. The Japanese raided the meeting place of this group and caught some of the members but Renato was able to escape through a backroom window. Soon after his marriage to Letizia Roxas in 1943, Japanese soldiers raided the couple's home. Luckily, Renato was not there. He and his family spent the rest of the Japanese occupation hiding in different towns and barrios of Bulacan.

[edit] Career Renato Constantino had several successful careers as a diplomat, a college professor, a museum director, a journalist and an author of many books. He was the Executive Secretary of the Philippine Mission to the United Nations from 1946 to 1949 and Counsellor of the Department of Foreign Affairs from 1949 to 1951. He published a book on the United Nations in 1950. His career in the academe spans more than three decades during which time he taught in Far Eastern University, Adamson University, Arellano University and University of the Philippines, Manila and Diliman.

He was also a visiting lecturer in universities in London, Sweden, Japan, Germany, Malaysia and Thailand, and visiting scholar in several other countries. As a journalist between 1945 and 1998, he was a columnist of the Evening Herald, Manila Chronicle, Malaya, Daily Globe, Manila Bulletin, and Balita. He also served as Director of the Lopez Memorial Museum from 1960 to 1972, was a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Contemporary Asia, and Trustee of Focus on the Global South in Bangkok.

Constantino was a prolific writer. He wrote around 30 books and numerous pamphlets and monographs. Among his well-known books are A Past Revisited and The Continuing Past (a two-volume history of the Philippines), The Making of a Filipino (a biography of Claro M. Recto), Neo-colonial Identity and Counter-Consciousness, and The Nationalist Alternative. Several of his books have been translated into Japanese and The Nationalist Alternative has a Malaysian translation.

[edit] Legacy His writings invariably reflected his nationalist, democratic, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist perspective whether he was writing historical articles or articles on the economy, Philippine society and culture. Because of what were then regarded as his radical views and his criticisms of those in power, he was persecuted many times in his life. He lost his position in the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1951 and thereafter he was prevented from getting a job because intelligence agents discouraged employers from hiring him on the ground that he was a security risk.

Off and on during his life, his articles were refused by major papers which used to print his works. In fact, his most widely read essay, The Miseducation of the Filipino, had to wait five years before it saw print. A few years before martial law, he was frequently criticizing Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos in his columns. These columns were published in a book, The Marcos Watch, just two weeks before Marcos declared martial law. When martial law was declared, he was placed under house arrest for seven months and not allowed to travel abroad for several years.

Recognition of Constantino's work came in his later years, among them Nationalism awards from Quezon City in 1987, Manila in 1988, The Civil Liberties Union in 1988, and U.P. Manila in 1989. These were followed by Manila's Diwa ng Lahi Award in 1989, a Doctor of Arts and Letters (honoris causa) from the Polytechnic University of the Philippines in 1989 and a Doctor of Laws (honoris causa) from the University of the Philippines in 1990.

Renato Constantino died on September 15, 1999.

Historian, Nationalist

Among the strongest influences in his youth was his maternal grandmother who told him stories about the abuses of Spanish friars. Her family suffered during the early American occupation. His father was critical of politicians of his time for their corruption and lack of sincerity in fighting for independence. Renato's siblings reported that although their parents were strict and expected unconditional obedience, their brother would sometimes dare to argue with them when he did not agree with their opinions.

A product of the public school system, Renato emerged as a student leader during his third and fourth years in Arellano High School when he was elected class president and also won medals as an orator and debater. In the University of the Philippines he became the youngest editor of the Philippine Collegian and a star debater. He won national attention with an editorial critical of President Manuel Quezon which prompted the latter to go to UP to deliver a speech explaining his position.

Renato fought in Bataan and was later sent by G2 to Manila to join a group that was monitoring Japanese military movements and sending reports to Corregidor. The Japanese raided the meeting place of this group and caught some of the members but Renato was able to escape through a backroom window. Soon after his marriage to Letizia Roxas in 1943, Japanese soldiers raided the couple's home. Luckily, Renato was not there. He and his family spent the rest of the Japanese occupation hiding in different towns and barrios of Bulacan.

[edit] Career Renato Constantino had several successful careers as a diplomat, a college professor, a museum director, a journalist and an author of many books. He was the Executive Secretary of the Philippine Mission to the United Nations from 1946 to 1949 and Counsellor of the Department of Foreign Affairs from 1949 to 1951. He published a book on the United Nations in 1950. His career in the academe spans more than three decades during which time he taught in Far Eastern University, Adamson University, Arellano University and University of the Philippines, Manila and Diliman.

He was also a visiting lecturer in universities in London, Sweden, Japan, Germany, Malaysia and Thailand, and visiting scholar in several other countries. As a journalist between 1945 and 1998, he was a columnist of the Evening Herald, Manila Chronicle, Malaya, Daily Globe, Manila Bulletin, and Balita. He also served as Director of the Lopez Memorial Museum from 1960 to 1972, was a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Contemporary Asia, and Trustee of Focus on the Global South in Bangkok.

Constantino was a prolific writer. He wrote around 30 books and numerous pamphlets and monographs. Among his well-known books are A Past Revisited and The Continuing Past (a two-volume history of the Philippines), The Making of a Filipino (a biography of Claro M. Recto), Neo-colonial Identity and Counter-Consciousness, and The Nationalist Alternative. Several of his books have been translated into Japanese and The Nationalist Alternative has a Malaysian translation.

[edit] Legacy His writings invariably reflected his nationalist, democratic, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist perspective whether he was writing historical articles or articles on the economy, Philippine society and culture. Because of what were then regarded as his radical views and his criticisms of those in power, he was persecuted many times in his life. He lost his position in the Department of Foreign Affairs in 1951 and thereafter he was prevented from getting a job because intelligence agents discouraged employers from hiring him on the ground that he was a security risk.

Off and on during his life, his articles were refused by major papers which used to print his works. In fact, his most widely read essay, The Miseducation of the Filipino, had to wait five years before it saw print. A few years before martial law, he was frequently criticizing Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos in his columns. These columns were published in a book, The Marcos Watch, just two weeks before Marcos declared martial law. When martial law was declared, he was placed under house arrest for seven months and not allowed to travel abroad for several years.

Recognition of Constantino's work came in his later years, among them Nationalism awards from Quezon City in 1987, Manila in 1988, The Civil Liberties Union in 1988, and U.P. Manila in 1989. These were followed by Manila's Diwa ng Lahi Award in 1989, a Doctor of Arts and Letters (honoris causa) from the Polytechnic University of the Philippines in 1989 and a Doctor of Laws (honoris causa) from the University of the Philippines in 1990.

Renato Constantino died on September 15, 1999.